Introduction: Amid the Chaos of Multiple Scandals Plaguing the Presidency, A New Threat to the American Way of Life, Conservatives, and Libertarians Has Emerged

The topic of immigration reform is reaching a fever pitch amid the chaos surrounding the Obama administration being embroiled in five scandals, of which four have been allowed by the liberal mass media to become common knowledge: the IRS's targeting of conservative tax-exempt groups; the Justice Department subpoenaing documents and news source material from The Associated Press and attempts to brand Fox News correspondent James Rosen "a conspirator" for exposing state department secrets in what Obama Press Secretary Jay Carney referred to as a breach of national security; the Benghazi negligence and cover-up by the State Department under the direction of Hillary Clinton; the EPA targeting conservative businesses and organizations, which has only drawn minimal coverage by such media outlets as Fox News and The Blaze, both of whom are conservative and/or libertarian leaning; and finally, the issue that has divided lawmakers not along party lines, but within the party ranks themselves, namely the NSA spying and surveillance program known as PRISM.

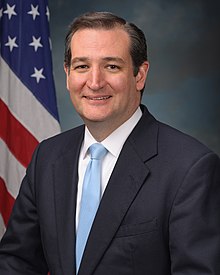

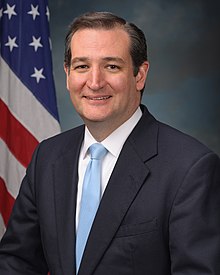

(Above: U.S. Senator Ted Cruz, R-TX. Courtesy of Wikipedia)

The prospects behind the proposed bill for immigration, which essentially creates a path to citizenship in what amounts to an act of amnesty by the federal government for illegal aliens, are dangerous toward the end of the founding virtues of America today. It is estimated that should this measure be passed -- and no doubt it will because it has widespread bipartisan support from all the Democrats in both the Senate and the House, as well as moderate Republicans such as Sens. John McCain, Lindsey Graham, and Marco Rubio, a man many believe will run for the GOP nomination for president in 2016. The latter's presidential nomination by the GOP hinges on the nomenclature and verbiage, how the bill will be crafted by his participation in the bipartisan senatorial cabal referred to as "The Gang of Eight," and furthermore, what provisions it will promote for the security of our borders, particularly with Mexico, but also with Canada and those arriving from overseas. Critics such as Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) decry the bill as favoring unconditional universal amnesty. It was Sen. Cruz in fact who was quoted on March 24, 2013 with these words in protest to this then-fledgling debate that has now morphed into a soon-to-be realized stark reality for Republicans:

"I have deep, deep concerns about a path to citizenship for those who are here illegally. I think creating a path to citizenship is No. 1,inconsistent with the rule of law. But No. 2, it is profoundly unfair to the millions of legal immigrants who have waited for years and sometimes decades in line to come here legally."

America is a nation built upon the backs of immigrants, and has been since the earliest English settlement at Roanoke in present-day North Carolina in 1587. Still, though, everything comes in moderation and within the rule of law. The Democratic Party has long disregarded constitutional laws that have governed the American people since the federal government opened its doors in Philadelphia in 1789. While he was not a socialist, as modern-day socialism did not exist in domestic politics in the years spanning from 1829-1837, Andrew Jackson as president increased the role of the executive branch so colossally that he was branded by his opposition party opponents, the Whigs, as "King Andrew." While the list of grievances for which the Democrats have been responsible is long and numerous, I do not have the time to sit here and write of every single one, as it has already taken me majority of the day with occasional breaks for breakfast, lunch, a nap, and dinner to author this piece.

The subsequent material will cover a number of aspects of the principles leading up to this latest controversy in President Obama's attempts to usurp control from the Constitution by developing a nation filled with illegal immigrants who were universally-granted amnesty to the tune of 30 million, who will prevent already-legal residents of the United States from being able to attain work due to these immigrants' willingness to labor for rock-bottom wages. Ultimately, the goal of the Democratic Party is not in its attempt to goad the American people into believe that its intentions of recognizing these illegal aliens is an act merited out of social justice and benevolence, but rather the creation of 30 million new American citizens who, through the Obama administration's designs of unconditional and universal amnesty, will vote as a block for politicians running for public office on the Democratic ticket. It is an attempt at wresting power through what 16th Century Italian political philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli called "extra-constitutional measures" away from their conservative opposition within the Republican and Libertarian Parties who seek to maintain the status quo in America by not promoting class warfare. Not only is there dissent over this among the parties, there is an equal amount of disagreement among Republican senators about the characteristics the bill should contain. And Democrats not only wish to not strictly patrol our borders, this wish to transfer those funds to other, more insidious measures. In one instance, Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA) wants to divert the funds the GOP senators wish to use to secure our borders toward funding public healthcare for immigrants granted citizenship. You can read more about it below (Courtesy of Mr. Conservative):

Sen. Boxer: Take Money To Build Border Fence And Spend It On Immigrant Healthcare

AUTHOR Warner Todd Huston

JUNE 16, 2013 12:07PM PST

California Senator Barbara Boxer has a great idea. Let’s take all that darn money away from border security and instead spend it on freebie healthcare for illegals. Great, huh?

This moron Democrat is planning on introducing an amendment to the Senate’s immigration bill that will redirect funds from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and spend it on entitlements to the illegals who will miraculously become full citizens with the Senate’s bill.

Current supporters of the amnesty bill claim that these new “citizens ” won’t be eligible for welfare and entitlements, but here comes Boxer to show us what Democrats really want to do. As it is, we already have illegals receiving $4 billion in government assistance a year. That will grow exponentially with this amnesty business.

And how are we to find all these people? We already know that Obama’s DHS can’t locate 266 dangerous criminal aliens already.

Boxer claims that her amendment will also be funded by the “fines” that these sudden Americanos will pay when applying for their citizenship. But, as in all government claims that massive amounts of tax dollars that will supposedly come from some new scheme, this won’t be likely occur. These “fines” will not likely amount to much if we ever see any of them, and the payments certainly would never be enough for a permanent new entitlement.

Boxer plans on her new freebie healthcare program to illegals to be a permanent program and even if the new citizens pay their “fines” it’ll be a one shot deal. Paid once and done. So, where will the rest of the money come from for the continuing freebie program? Yep, our taxes.

The current bill claims that these newly legalized people won’t be eligible for federal welfare programs for 15 years. But, naturally, Boxer’s amendment nixes that idea in favor of near immediate welfare assistance.

The fact is this bill will create two things, both likely permanent. First it will create a permanent underclass that will never really become Americans (as in assimilating as true, practicing Americans), people who will stay poor forever. Second it will create a permanent Democrat majority as this class of people clamor for ever more welfare and tax money for themselves… and will now wield the power of the vote to get it. And the Democrat Party will be happy to keep giving it to them in order to stay in power.

Worse we are seeing lie after lie from Democrats. Obama, for instance, has already lied when he claimed that the bill would require illegals to learn English.

The first solution to the immigration problem is to close off the southern border. Tight as a drum. Then we can start talking about what else to do with those that decide to stay here. It really is foolish to even bother talking about anything until that happens first.

What do you think of the path to citizenship? Me, I am not inherently against it, but this new plan is NOT the way to go.

--

It is in times like today that Anglo-American philosophe Thomas Paine of the 18th Century Enlightenment, who authored such works as Common Sense and The American Crisis, both of which were published in 1776, wrote in the latter pamphlet the following iconic phrase:

"These are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as freedom should not be highly rated."

With the current quartet of acknowledged scandals that I mentioned above attached to the past six months worth of the Obama administration's and the Democrats in Congress' attempts at subverting the American people's right to bear arms via the Machiavellian-defined method of "extra-constitutional measures," our civil liberties are under attack. Furthermore, not only have income taxes been increased universally across all levels of income, including the middle-class and the poor, by the Obama administration through his sequester and the proposed 2014 budget twice within the past six months, lifelong citizens of the U.S. stand a chance of losing the opportunity to attain gainful employment due to the proposal laid out before Congress, which is being debated intensely within the Senate. And with the approaching date quickly approaching for the full-initiatives and policies of the Affordable Health Care Act (aka. "Obama Care") to be implement in 2014, unemployment is projected by economists to skyrocket over the course of the next 10 years to the tune of at least 800,000 lost jobs as a result of layoffs due to both small businesses running out of business and major corporations not being able to afford the health care premiums. One news report I read stated that the administration is not only intent on arming the Free Syria Army, which slaughtered a village populated solely by Christians, but is also planning on deploying 20,000 +/- troops to the embattled Arab state under the guise of liberating Syria from the tyranny of President Bashar al-Assad. Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) has long been the president's most vocal opponent on all of his policies; he is now being attacked by members of the Democratic Party and the left-wing mass media as being "untrustworthy" and "dangerous" because he is now considered to be the single greatest threat posed by any Republican politician since Ronald Reagan.

In segueing into the next phrase of my article, I will give you a brief account on some of the Founding Father's statements reflecting their personal convictions on liberty, the intangible object coveted by the majority of the world except for those of the Left in North America and Europe. America was founded upon the principles which, in part, will be described below when I provide the one of but a slew of famous lines from the quill pen of Thomas Jefferson as he drafted the Declaration of Independence beginning in late June 1776 and concluding with its signing and ratification on July 4. The other comment which describes the principles behind the purpose of, and the victory, the American Revolution engendered the possibility of the founding of America is stated by another of the Founders, John Adams, who claimed that the then-fledgling republic was formed upon the following principles in a letter to Jefferson dated June 28, 1813 (Courtesy of The Founders):

Through the annals of history come the lessons replete with the philosophies upon which "the great experiment" as James Madison referred to the early American republic were founded. With the principle of Christianity as the primary basis for our founding currently in great jeopardy of being extinguished by the current president, we must declare war on the Left by any means necessary, first with our remaining liberties; then with our votes. Finally, should all options be exhausted and still we are faced with the annihilation of the American rights to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," we must, according to Jefferson, "replenish" the "tree of liberty" with "the blood of patriots and tyrants," for according to the paramount Founding Father, "It is its natural manure."

--

A Brief History Regarding the Founding Fathers and Other Notable Figures of Our History Philosophies on Liberty and the Concept of Individualism Which Emanates From It

In his Historical Review of Pennsylvania published in 1759, Benjamin Franklin made this comment that I now believe to be the most important quote of the pre-Revolutionary War era with regards to liberty in America's history:

"Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety."

These words, as with many recorded from the quill pens and speeches delivered by future Founding Fathers, would be declarative of the American revolutionary spirit which officially sparked its powder keg on April 19, 1775 with the Revolution's first battle located outside Boston, MA, in the adjacent cities of Lexington and Concord. We see at this juncture among the very first examples in Anglo-America's documented 426 year history beginning with the first settlement at Roanoke Island in present-day Dare County, North Carolina that was financed by Sir Walter Raleigh and settled finally by John White on July 22, 1587. His granddaughter, Virginia Dare, was the first to be born in the Anglo-American colonies in the New World. It was, indeed, during the British troops' march toward Lexington and later Concord that Paul Revere endeavored on his now-iconic ride, which as legend states him shouting from a top his horse, "The Red Coats are coming!" The purpose behind this endeavor was simple, and serves as the principle behind the argument induced by conservatives and libertarians today with regard to the Second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America located within the Bill of Rights: the British regulars under the lead of Major John Pitcairn marched toward Lexington and Concord with the intention of confiscating the local militia's stored firearms. It was this that served as the impetus to war, a conflict that had originally been manifested according to The Independence Institute's research director David B. Kopel, but through coercion and an attempt to subjugate the colonists of Boston and the rest of Massachusetts that had been declared by the British Parliament as being engaged in a state of rebellion, became "a shooting war" that would ultimately last for the next eight years in one form or another, with the last major battle at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781 ending the bulk of the hostilities, but the Treaty of Paris not being signed by both the fledgling United States and the British government until 1783.

The lust and seductiveness of the American patriotic spirit lives on today in fewer than half of the registered voters domestically. Over the past 120 years since the initiation of the Progressive and Populist political movements, the size, reach, and scope of government, once held in close check by all political parties including the Democrats, which was founded by former adherent to the Jeffersonian ideologies that imbued the first successful political party known as the Democratic-Republican Party in former Tennessee U.S. congressman and senator and War of 1812 hero at the Battle of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson, has now become a colossus that has engulfed the American stream of consciousness once enveloped in the principles of liberty through the theme one may find within the preeminent Transcendentalist poet Ralph Waldo Emerson's eternal essay now sacred to conservatives and libertarians in its symbolism of what America was and should still be, Self-Reliance. Two very famous quotes can be found from Emerson's masterpiece:

"It is said to be the age of the first-person singular."

The above-quote is richly-endowed in its reflection of traditional conservative and libertarian values pertaining to the rights of the individual, which is in direct contradiction to the opposite half of the dichotomy the Left represents: namely that of the collective, the concept whereby a person is enlightened who raises his or her fist, clinched, and declares in a raised voice, "Power to the People!"

The other phrase is as follows:

"Nothing at last is sacred but the integrity of your own mind."

This quote once reflected the God-given entitlement guaranteed first by English political philosopher John Locke in his radical work from the 17th Century titled Second Treastise on Civil Government whereby he proclaimed that it was government's job to serve its people rather than the people's preoccupation in serving the government. His most famous phrase influenced America's greatest Founding Father, Thomas Jefferson, in his drafting of the Declaration of Independence during the summer of 1776, stating that all people have the God-given rights to "life, liberty, and property." So moved was Jefferson by this line that he rephrased it but very little little in the Declaration, subtly changing it to "the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Locke was the impetus for majority of the revolutionary thinking during the 20th Century political phenomena that produced the philosophes, popularly referred to as the Enlightenment in Europe and the American colonies. His legacy was propagated by the works of such notable philosophes as David Hume, Voltaire, Denis Diderot in his Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (English: Encyclopedia or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts and Crafts), Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, and the fathers of the two modern political ideologies in the Western world: French-Swiss philosophe Jean Jacques Rousseau, who through such works as A Discourse on Inequality and his most famous political treatise The Social Contract, manifested over the course of the mid-18th Century the principles embodied today by socialism as espoused by the Left, the latter work which influenced to a small degree the American Revolution and was the primary source material behind the principles of the French Revolution; and Irish-British philosophe Edmund Burke, who served in the British Parliament for many years and founded what would become known as modern conservatism, basing his principles largely upon those of the classical liberalism espoused by Locke. These concepts spilled over into America and, as stated before, greatly influenced the "Spirit of 1776," whereby a people subjugated to the whims of its masters some 5,000 miles away across the Atlantic in a parliamentary setting while not itself being allowed to elect members to serve in that legislative body in order to engage in the act(s) of lawmaking chose to fight for their independence rather continue down the path of a slippery slope toward a posterity filled with discontent.

For more than 115 years subsequent the founding of the republic by virtue of the signing of the Declaration on July 4, 1776, America largely lived by the principles initiated by the Founding Fathers with few exceptions. In some instances, the nation became legally-freer when slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment, but it took a bloody civil war and the deaths of more than 600,000 Americans both on the Federal and Confederate sides to officially end "the peculiar institution" that was the very embodiment of evil within our nation since the English founded the colonies of Roanoke in 1587 and Jamestown in 1607. But around 1890, a new form of civil unrest and political radicalism materialized in the form of a rising political culture we today through the reading of history and putting two-and-two today know as the Left. This new political phenomena was brought to America by the immigrants of the day, a phenomena that while it had always been a prevalent and accepted norm domestically since the founding of the Anglo-American colonies in the centuries prior to then, began to fundamentally alter the political landscape in the United States, and it ultimately succeeded in its endeavors. The first two political movements to advocate the principles of the new Left in America were the Populists and the Progressives. Among the famous advocates for such political principles being applied into public policy were William Jennings Bryan, W.E.B. Du Bois, Eugene V. Debs, and also included future presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. Bryan was the most notable Populist Party member (aka. the People's Party) to serve in high office, doing so as a Democrat, which according to Wikipedia "[the party platform was based among] poor, white cotton farmers in the South (especially North Carolina, Alabama, and Texas) and hard-pressed wheat farmers in the plains states (especially Kansas and Nebraska), it represented a radical crusading form of agrarianism and hostility to banks, railroads, and elites generally [and] sometimes formed coalitions with labor unions." Furthermore, "[t]he terms 'populist' and 'populism' are commonly used for anti-elitist appeals in opposition to established interests and mainstream parties."

As such, the Populists were one of the two initial political entities that would evolve into the modern-day left-wing Democratic Party; the other party, or more along the lines of activists, to promote such change and did so with great success, were the Progressives. The legacy of the Progressive movement, an era most scholars tend to date as having been in existence from 1890-1922, foreshadowed today's Democratic Party like a cabal of hovering albatrosses flying over their heads. While it is certainly true that the Populist Bryan achieved rock star-like idolatry among his constituents in his home state of Nebraska as well as other states within the Great Plains and in the South where poverty among farmers was prevalent as well as he was elected or appointed to public office; was a noted as "The boy orator from the Platte" for his fiery skills he displayed as an artful orator and debater; and his service in public office, most notably as Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson, the Populist Party was short lived and never achieved its goals of fundamentally transforming American politics. The same could not be said accurately regarding the Progressives however. The Progressive movement was initiated during the 1890's and by 1901, with the ascension of Theodore Roosevelt to the office of president of the United States upon the assassination of his predecessor William McKinley completing the assimilation of the activist movement into the political mainstream and public policy. Theodore Roosevelt, a member of the Republican Party, was the first strong and aggressive president since the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, as "Honest Abe's" successors were lacking in charisma and initiative in the years following the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1863. With the U.S.'s landmark victory over a major European imperial power in the form of Spain during the Spanish-American War of 1898 came the spoils of victory: America became a legitimate empire, with territories located in the Pacific Rim within the continental regions of Asia (the Philippines) and Oceania (Hawaii as a result of the revolt led by U.S. Marines against the ruler, Queen Liluokalani; as well as Guam, which came along with the territories acquired from Spain), and in the Caribbean Sea (Cuba and Puerto Rico). Roosevelt promoted the great power of the U.S. Navy, which he dubbed "The Great White Fleet," and deployed it to ports of call worldwide to display America's military might. He also was chiefly responsible for the policy of building the Panama Canal during the first decade and a half of the 20th Century. Yet it is his domestic policy that seems to draw more parallels to today's modern Democratic Party according to a number of scholars. Roosevelt was noted for ramming legislation through Congress and signing into law measures that curtailed corporate monopolies, thus gaining notoriety as "the trust buster." He implemented several policies championed for years by Progressives such as agencies to assure the safe manufacture of products in factories, laws which regulated working conditions, etc. It is thus ironic to consider that the first modern liberal president was, in fact, a Republican. Let it also be known that since the Presidential Election of 1828 that pitted incumbent John Quincy Adams against the founder of the newly-formed Democratic Party in Andrew Jackson, the Democratic platform has evolved greatly over said-period of time. What once was a party predicated on the notion of limited government, greater adherence to civil liberties in accordance to the Bill of Rights of the Constitution, and the prevalent belief in states' rights and even the right to nullification of laws that state governments found to be unconstitutional due to their violation of their Tenth Amendment rights that was originally espoused by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in their Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 that ultimately propagated and perpetuated the institution of slavery in the South as well as during the admission of new states to the Union. (The concept of states' rights and nullification arose during the processes that produce the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Compromise of 1850, and finally the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 that ultimately exhausted all attempts that ultimately proved to be fruitless in averting what Jefferson in 1819 determined the controversy over slavery as being "a firebell in the night.") The Democratic Party, which historians and political scholars claim rose from the ashes of its previous incarnation accredited to have been Jefferson's own Democratic-Republican Party of the First Party System that was founded in 1793 and therefore would make technically mean that the party is not only the oldest in continual existence in the U.S. but one of the world's oldest as well, was the party of slavery and, ultimately, racism and bigotry, whose reputation as such remained a prevalent typecast until 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 within the company of civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The final merger between the Progressives and a major political party took place during the Presidential Election of 1912, when Woodrow Wilson was elected. The race was a three-way affair between incumbent William Howard Taft, who had been anointed as the chosen successor to the presidency by Theodore Roosevelt; Roosevelt himself, who was dissatisfied with Taft for undoing many of his Progressive policies during his term as president and therefore decided to run as a member of his won political party, the Progressive Party (aka. "The Bull Moose Party"), and of course Wilson on the Democratic ticket. While Roosevelt acquired more votes than any other third party candidate in the history of the presidential electoral process, he was unsuccessful and therefore surrendered the mantle as champion of the Progressive cause to Wilson, who held the advantage of being a candidate of a major party who happened also to be a Progressive ideologue. Among the first orders of business during the Wilson administration were the passage of two constitutional amendments in 1913: the Sixteenth Amendment, which created a permanent progressive federal income tax; and the Seventeenth Amendment, which altered the method in which U.S. senators would forever be elected by allowing the general population to vote for the senator of their choice in the general elections instead of their appointment to their positions being determined by the state legislatures. Lastly, as part of Wilson's sweeping domestic policies that further increased the size and reach of the federal government, he signed into the law the Federal Reserve Act that created the central banking institution that has becoming chiefly responsible for the monetary policies with regards to controlling inflation and interest rates over the course of the past 100 years. Wilson also lied to the American people in 1914 by reneging on his pledge to keep the nation out of World War I in Europe; his campaign slogan in 1916 even predicated his message with the propagandized slogan, "He kept us out of war." Unfortunately, with the sinking of the H.M.S. Lusitania by German U-boats and the retrieval of the Zimmermann Telegram between the German Empire and the government of Mexico where Germany allegedly promised to return the lands lost to the U.S. in the Mexican War, the Battle for Texas Independence, the revolt in California led by John C. Fremont, the first Republican Party candidate for president and one of the first settlers and founders of the Bear Republic, known today as California, President Wilson convinced Congress in 1918 to declare war on Germany. The U.S. would sustain a total of 310,518 casualties, of which 116,516 were killed in combat during the one year of participation in the war.

Following Wilson's presidency with the election of Republican Party candidate Warren G. Harding in 1921, the U.S. experienced a period of great economic prosperity during the decade that became known as "The Roaring Twenties." Income tax rates for the wealthiest Americans were cut from the previous high of 75% during 1916-17 down to 25% during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding upon his death in 1923. However, with the big government policies of Herbert Hoover, who prided himself as being a disciple of the Progressive Era, resulting in another great increase in federal regulations and an increase in taxes of various assortments, the Stock Market crashed on October 29, 1929, the day the American people would rue for years to come by referring to it as "Black Tuesday." In response to the crisis that at the height of what would become known to history as The Great Depression, the Democratic Party further assimilated with the ideology of Progressive politics when Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president in 1932 in a landslide over the incumbent Hoover. Roosevelt fundamentally changed not just the Democratic Party, but the face of American politics forever by introducing measures such as his New Deal legislative acts such as Social Security and other forms of public subsidies and federal entitlement expenditure programs, dozens of federal regulatory agencies, and federally-funded public employment apparati such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) that ushered in a new and seemingly-permanent era of domestic policies creating the modern-day welfare state and socialist politics in America that had already spread through Europe first with the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 that resulted in the rise of the first Communist government in world history and then in the 1920's with the economies of Western Europe experiencing depression-like symptoms turning to a different breed of the practice commonly referred to as "democratic socialism," or "social democracy." It is the latter form of socialism into which the U.S. transformed, though various quotes stated by FDR (abbreviation of Franklin D. Roosevelt in a concerted effort to avoid confusing him with his fellow family member, former President Theodore Roosevelt) suggests to scholars that he was, indeed, a proponent to, for, and of the ideology of Communism as was conceptualized by Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels in their groundbreaking political treatise that would influence more than half the governments of the world that would rule more than 50% of the global population under the hegemony of the Soviet Union in their works The Communist Manifesto (1848) and the solo Marxist work many call his true masterpiece even over the a fore mentioned treatise called Das Kapital (1867). One day, I hope to revisit The Communist Manifesto, which I read in two different classes in college (History 319: The History of Modern Europe, 1750-1919; and Political Science 479: The Study of Modern Political Thought in Western Civilization From Machiavelli to the Present), before attempting to tackle Das Kapital, a work I understand to be rather laborious to undertake and far more arduous a read than that of the cooperative effort of Marx and Engels.

It should be noted that Roosevelt's methods for attempting to resurrect the prosperity of the American economy were derived by the postulations posited by the first major economic theorist in the West originating in the United Kingdom whose name was John Maynard Keynes. Keynes was the first proponent of macroeconomics, an ideology that broke ranks from the long-accepted and thus adopted theories placed in 1776 by another British economist, Adam Smith, in his groundbreaking pamphlet on political economics formally titled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, or more commonly referred to simply as The Wealth of Nations. It is in Smith's commentary where the world is introduced to the concept of laissez-faire economics, translated from French into English as "the invisible hand." Smith advocated for an economic policy free and unfettered from exorbitant government regulations, citing that through these means as well as through low tariffs and lower taxes, an economy has limitless potential for extraordinary growth that trickles down to the people who encompass it standing to gain in pecuniary affluence and thus provides them the avenue of social ascension through said-phenomena. Where Smith endeavored to propagate his truth, and the truth as it has since born out over the past 33 years since the revival of conservatism in Western democracies beginning in 1979 with the election of Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister of Great Britain for the Conservative Party and emergence of "The Reagan Revolution" during the 1980's in supplanting the following's failed economic theorems, Keynes advocated more government involvement with regards to adjusting interest rates, levels of taxation, engaging in deficit spending, providing for the public good through public expenditure programs, and finally promoting the welfare state, in controlling the ebb-and-flow of economic trends between bull and bear markets. The popular myth that has long been propagated by the Left domestically is that through socialism and the creation of the welfare state, FDR brought America out of The Great Depression. The truth is, however, quite contradictory to the myth: while it is true that the rate of unemployment decreased from 25% in his first year in office (1933) to 14% in 1935, he accomplished this by creating low-paying jobs in organizations and industries owned by the federal government. Whereas socialism generally means the acquisition of property and the vast majority of means of production by the state, capitalism, which FDR greatly distrusted, declares the contrary to be true, that the fruits of one's own labor inherently belong the laborer. According to Smith in Book 1, Chapter VIII of The Wealth of Nations, he makes the following claims with regard to this concept:

"In that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master to share with him."

Through this passage, we have an allusion to the concept of natural law, one of the two principles upon which a free people can, should, and would found a free society. The exact diction and method for syntax was brilliant in its simplicity and flow. Jefferson employed it precisely in this manner:

"...the Laws of Nature and Nature's God...."

What, then, do we derive from the theory FDR and every member of the socialist establishment in the West over the past 90-100 years have employed with regard to the right of the worker to the fruits of his or her own labor? Smith discusses more within that section of his work:

"What are the common wages of labour, depends everywhere upon the contract usually made between those two parties, whose interests are by no means the same. "The workmen desire to get as much, the masters to give as little as possible. The former are disposed to combine in order to raise, the latter in order to lower the wages of labour."He continues on:

"It is not, however, difficult to foresee which of the two parties must, upon all ordinary occasions, have the advantage in the dispute, and force the other into a compliance with their terms. The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily; and the law, besides, authorizes, or at least does not prohibit their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work; but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes the masters can hold out much longer. A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, a merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired without employment. In the long run the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him; but the necessity is not so immediate.

"We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combination of masters , though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate. To violate this uniform combination is everywhere a most unpopular action, and a sort of reproach to a master among his neighbours and equals. We seldom, indeed, hear of this combination, because it is usual, and one may say, the natural state of things, which nobody ever hears of. Masters, too, sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate. These are always conducted with the utmost silence and secrecy, till the moment of execution, and when the workmen yield, as they sometimes do, without resistance, though severely felt by them, they are never heard of by other people. Such combinations, however, are frequently resisted by a contrary defensive combination of the workmen; who sometimes too, without any provocation of this kind, combine of their own accord to raise the price of their labour. Their usual pretences are, sometimes the high price of provisions; sometimes the great profit which their masters make by their work. But whether their combinations be offensive or defensive, they are always abundantly heard of. In order to bring the point to a speedy decision, they have always recourse to the loudest clamour, and sometimes to the most shocking violence and outrage. They are desperate, act act with the folly and extravagance of desperate men, who must either starve, or frighten their masters into an immediate compliance with their demands. The masters upon these occasions are just as clamorous upon the other side, and never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combinations of servants, labourers, and journeymen. The workmen, accordingly, very seldom derive any advantage from the violence of those tumultuous combinations, which, partly from the interposition of the civil magistrate, party form the necessity superior steadiness of the masters, partly from the necessity which the greater part of the workmen are under of submitting for the sake of present subsistence, generally end in nothing, but the punishment or ruin of the ringleaders."

From this description that seems to be Smith's unintentionally prophesying the advent of the Marxist Communist ideology that would lead to nearly 75 years of more than half of the world's population living beneath the subjugation of the "sickle and hammer," he arrives at the final conclusion with regards to the relationship between "masters" and "labourers":

"But though in disputes with their workmen, masters must generally have the advantage, there is, however, a certain rate below which it seems impossible to reduce, for any considerable time, the ordinary wages even of the lowest species of labour."

To the untrained eye of novice students, one may construe this to imply that Smith is advocating the implementation of what the Left in Western nations refer to as a "living wage," aka. "the minimum wage." However, his economic philosophy, again, was laissez-faire, and he espoused less government controls on the economy and thus in the lives of the workers. Smith refers to this "certain rate below which it seems impossible to reduce, for any considerable time, the ordinary wages even of the lowest species of labour" as a naturally-occurring phenomena within a free-market capitalist economic system. The Left, beginning with the philosophies of Marx in his cooperative work with Engels The Communist Manifesto and later in his solo treatise Das Kapital, proposed to place price controls on the costs of goods and services within society and economic factors via raising taxes and tariffs. Smith was similar to Marx and Engels in his being the first modern economist to propose a progressive tax based in proportion on the incomes of each individual within a society. What he did not advocate or even imply was to tax the people of a society beyond their capacity to pay. This practice that Communist nations within the Soviet Union's sphere of influence and the socialist democracies of Western Europe and North America implement as public policy have greatly inhibited and stifled economic growth and the pursuit of widespread wealth and prosperity under the pretense of what President Barack Obama stated to the man now known as "Joe the Plumber" in 2008 of his support for the federal government to "spread the wealth."

Benjamin Franklin, who I quoted above with regards to relinquishing "essential liberty" under the pretenses of "temporary security," also stated the following in his commentary On the Price of Corn and Management of the Poor from November 29, 1766:

"I am for doing good to the poor, but I differ in opinion of the means. I think the best way of doing good to the poor, is not making them easy in poverty, but leading or driving them out of it. In my youth I travelled much, and I observed in different countries, that the more public provisions were made for the poor, the less they provided for themselves, and of course became poorer. And, on the contrary, the less was done for them, the more they did for themselves, and became richer."

Furthermore, in a letter written to his close friend, political ally, and confidante James Madison on October 28, 1785 at his temporary residence Fontainebleau while serving as the U.S. Minister to France, Thomas Jefferson wrote his opinion on the state and nature of poverty as he saw it in French society, a problem of social inequity whose growing unrest ultimately led to the bloody violence of the French Revolution with the fall of the Bastille in 1789:

DEAR SIR,

-- Seven o' clock, and retired to my fireside, I have determined to enter into conversation with you. This is a village of about 15,000 inhabitants when the court is not here, and 20,000 when they are, occupying a valley through which runs a brook and on each side of it a ride of small mountains, most which are naked rock. The King comes here, in the fall always, to hunt. His court attend him, as do also the foreign diplomatic corps; but as this is not indispensably required and my finances do not admit the expense of a continued residence here, I propose to come occasionally to attend the King's levees, returning again to Paris, distant forty miles. This being the first trip, I set out yesterday morning to take a view of the place. For this purpose I shaped my course toward the highest of the mountains in sight, to the top of which was about a league.

As soon as I had got clear of the town I fell in with a poor woman walking at the same rate with myself and going the same course. Wishing to know the condition of the laboring poor I entered the mountain: and thence proceeded to enquiries [sic] into her vocation, condition and circumstances. She told me she was a day laborer at 8 sous 4d. sterling the day: that she ahd two children to maintain, and to pay a rent of 30 livres for her house (which would consume the hire of 75 days), that often she could no employment and of course was without bread. As we had walked together nearly a mile and she had so far served me as a guide, I gave her, on parting, 24 sous. She burst into tears of a gratitute which I could perceive was unfeigned because she was unable to utter a word. She had probably never before received so great an aid. This little attendrissement, with the solitude of my walk, led me into a train of reflections on whcih I had observed in this country and is to be observed all over Europe.

The property of this country is absolutely concentrated in a very few hands, having revenues of from half a million of guineas a year downwards. These employ the flower of the country as servants, some of them having as many as 200 domestics, not laboring. They employ also a great number of manufacturers and tradesmen, and lastly the class of laboring husbandmen. but after all there comes the most numerous of all classes, that is, the poor who cannot find work. I asked myself what could be the reason so many should be permitted to beg who are willing to work, in a country where there is a very considerable proportion of uncultivated lands? These lands are undisturbed only for the sake of game. It should seem then that it must be because of the enormous wealth of the proprietors which places them above attention to the increase of the enormous wealth of the proprietors which places them above attention to the increase of their revenues by permitting these lands to be labored. I am conscious that an equal division of property is impracticable, but the consequences of this enormous inequality producing so much misery to the bulk of mankind, legislators cannot invent too many devices for subdividing property, only taking care to let their subdivisions to go hand in hand with the natural affections of the human mind. The descent of property of every kind therefore to all the children, or to all the brothers and sisters, or to other relations in equal degree, is a politic measure and a practicable one. Another means of silently lessening the inequality of property is to exempt all from taxation below a certain point, and to tax the higher portions or property in geometrical progression as they rise. Whenever there are in any country uncultivated lands and unemployed poor, it is clear that the laws of property have been so far extended as to violate natural right. The earth is given as a common stock for man to labor and live on. If for the encouragement of industry we allow it to be appropriated, we must take care that other employment be provided to those excluded from the appropriation. If we do not, the fundamental right to labor the earth returns to the unemployed. It is too soon yet in our country to say that every man who cannot find employment, but who can find uncultivated land, shall be at liberty to cultivate it, paying a moderate rent. But it is not too soon to provide by every possible means that as few as possible shall be without a little portion of land. The small landholders are the most precious part of a state.

The next object which struck my attention in my walk was the deer with which the wood abounded. They were of the kind called "Cerfs," and not exactly of the same species with ours. They are blackish indeed under the belly, and not white as ours, and they are more of the chestnut red; but these are such small differences as would be sure to happen in two races from the same stock breeding separately a number of ages. Their hares are totally different from the animals we call by that name; but their rabbit is almost exactly like him. The only difference is in their manners; the land on which I walked for some time being absolutely reduced to a honeycomb by their burrowing. I think there is no instance of ours burrowing. After descending the hill again I saw a man cutting fern. I went to him under the pretence of asking the shortest road to town, and afterwards asked for what use he was cutting fern. He told me that this part of the country furnished a great deal of fruit to Paris. That when packed in straw it acquired an ill taste, but that dry fern preserved it perfectly without communicating any taste at all.

I treasured this observation for the preservation of my apples on my return to my own country. They have no apples here to compare with our Redtown pippin. They have nothing which deserves the name of a peach; there being not sun enough to ripen the plum-peach and the best of their soft peaches being like our autumn peaches. Their cherries and strawberries are fair, but I think lack flavor. Their plum I think are better; so also their gooseberries, and the pears infinitely beyond anything we possess. They have nothing better than our sweet-water; but they have a succession of as good from early in the summer till frost. I am to-morrow to get [to] M. Malsherbes (an uncle of the Chevalier Luzerne's_ about seven leagues from hence, who is the most curious man in France as to his trees. He is making for me a collection of the vines from which the Burgandy, Champagne, Bordeaux, Frontignac, and other of the most valuable wines of this country are made. Another gentleman is collecting for me the best eating grapes, including what we call the raisin. I propose also to endeavor to colonize their hare, rabbit, red and grey partridge, pheasants of different kinds, and some other birds. But I find that I am wandering beyond the limits of my walk and will therefore bid you adieu.

Yours affectionately.

A common assessment of Jefferson is that he was a man of letters, of which he wrote approximately 18-to-20,000 by conservative estimates that historians have been able to retrieve. It is important to note his advocacy in this letter to co-ideologue James Madison of what amounts to not merely being a simple progressive form of taxation as was alluded to be the economist Smith, but an income tax placed "in geometrical progression" in accordance to one's level of acquisition of "higher portions or property."

However, Jefferson is more renowned for implementing a tax infrastructure that was less burdensome and repressive of a free-market, laissez-faire economic system that he considered to prohibitive and antithetical toward the conditions he promulgated as being favorable toward economic growth and the propagation of the people's natural right to what Locke referred to as "property" and for Jefferson "the pursuit of happiness" (Courtesy of The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History):

Monticello Dec. 15. 10.

Dear SirOur last post brought me your friendly letter of Nov. 27. I learn with pleasure that republican principles are predominant in your state, because I conscientiously believe that governments founded in them are most friendly to the happiness of the people at large; and especially of a people so capable of self government as ours. I have been ever opposed to the party, so falsely called federalists, because I believe them desirous of introducing, into our government, authorities hereditary or otherwise independant [sic] of the national will. these always consume the public contributions and oppress the people with labour & poverty. no one was more sensible than myself, while Govr. Fenner was in the Senate, of the soundness of his political principles, & rectitude of his conduct. among those of my fellow laborers, of whom I had a distinguished opinion, he was one: and I have no doubt those among whom he lives and who have already given him so many proofs of their unequivocal confidence in him, will continue so to do. it would be impertinent in me, a stranger to them, to tell them what they all see daily. my object too at present is peace and tranquility, neither doing nor saying any thing to be quoted, or to make me the subject of newspaper disquisitions. I read one or two newspapers a week, but with reluctance give even that time from Tacitus & Horace, & so much other more agreeable reading. indeed I give more time to exercise of the body than of the mind, believing it wholesome to both. I enjoy, in recollection, my antient [sic] friendships, & suffer no new circumstances to mix alloy with them. I do not take the trouble of forming opinions on what is passing among them; because I have such entire confidence in their integrity & wisdom, as to be satisfied all is going right, & that every one is doing his best in the station confided to him. under these impressions accept sincere assurances of my continued esteem & respect for yourself personally, & my best wishes for your health & happiness.Th: Jefferson

We should furthermore comprehend that while Jefferson was amenable to the terms of greater social egalitarianism in terms of economic stability and viability as well as each individual having within his means the prospects available to him for social and economic advancement, he opposed direct taxation, a form of which is the progressive income tax. Under the administration of John Adams (1797-1801), the nation's first experimentation with direct taxation, a practice reviled during the latter years of British hegemony when Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, was put into motion with duties placed upon land, slaves, and houses to cover the cost of the controversial XYZ Affair and the ensuing Quasi-War with France in 1797-98. This, along with the unconstitutional Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 which were passed by the Federalist Congress and signed into law by Adams, contributed directly to the downfall of the Federalist Party and Jeffersonian Revolution of 1800, which resulted in Jefferson's election as president.

Among Jefferson's primary goals were the following:

- Implement policies designed to decrease federal expenditures

- Achieving an annual balanced budget

- Paying down the federal deficit

- Alleviate the American people of the gross tax burdens that had become the law of the land under the Washington and Adams administrations

This would appear to contradict Jefferson's earlier dalliance with the direct progressive income tax. According to Tax Analysts, a site dedicated to the study of taxation in America both past and present:

"The latter two objectives seemed to conflict with one another; specifically, Jefferson's desire to abrogate Hamilton's funded debt plan and retire all government obligations as judiciously as possible required a steady stream of revenue.

"Nevertheless, Jefferson abolished all internal taxes, including the whiskey excise tax and the land tax. Meanwhile, the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, though a diplomatic minefield for American statesmen, proved a significant stimulus to the economy of the United States. Vigorous commerce enriched merchants while customs duties swelled the federal Treasury. By 1808 the national debt had been reduced from $80 million to $57 million, even though the Louisiana purchase had added an $11 million liability. By 1806, duties proved so lucrative that Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin and Jefferson fretted about what to do with the surplus above that required for debt retirement. Treasury reserves increased from $3 million to $14 million between 1801 and 1808."

It was a problem for Jefferson that virtually all successive presidents no doubt have come to envy, with the only time in U.S. history the federal deficit was ever paid off has been disputed depending on the source regarding whether or not it having ever actually occurred, as happening during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, who according to records, did so in 1835, two years prior to his exit from the White House. But after the 1932 election of FDR to the presidency, politics in America fundamentally changed forever, to where over the period of the past 80 years the American people have largely forgotten their nation's roots, derived from the blood, sweat, and toil of their forefathers and patriots, and whose principles of liberty were conceptualized by our Founding Fathers such as Franklin, Washington, Adams, Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison. Gradually, Americans have come to disavow the principles behind the fight for independence that led to the deaths of some 25,000 Continental Army soldiers and local militiamen who were the very epitome of patriots and the philosophies derived from ancient civilizations as well as the governments in Europe during the 100-200 years prior to the Revolution that our Founding Fathers packaged in with the essences Adams wrote in his June 28, 1813 letter to Jefferson that I posted above of "Christianity... and the general Principles of English and American Liberty" in favor of pure, unadulterated atheism, another of Adams' observations based upon his observations of vanity, vagaries, and societal and moral decadence that were as prevalent in 18th Century France during the years leading to the French Revolution as they are today in all the nations of Western civilization, including America. In the past 50 years, the New Atheists, whose plight and cause have been championed by the Democratic Party, have transformed America from "One Nation Under God" to one whereby a small minority dictates the social politics of the majority by instilling fear in the popular majority of litigious activity and even militant protests if their demands are not met. These new principles from the past half-century are true of other minority sectarian groups of the population. Thus, the demographic of the population in the majority has been exposed to a phenomenon tantamount to the National Party of South Africa's long-standing policy of Apartheid it implemented against the majority black population in the nation.

Addressing the Issue of Providing Unconditional, Universal Amnesty to Illegal Aliens and What the Founding Fathers Had to Say About the Institution of Immigration

The First Settlements in Anglo-America: The Ill-Fated Lost Colony of Roanoke (NC), Jamestown (VA), and Plymouth (MA)

As I stated above, the foundation of Anglo-America was based entirely on the strength of immigrants from the mother country of England. Also previously stated, the first settlement was at Roanoke in present-day North Carolina in 1587 by John White, who was funded by Sir Walter Raleigh. And it is also the case that while people inhabited the Roanoke Colony for the brief time it was in existence before the mysterious disappearance of all who lived there, the first newborn in English America was delivered. Her name was Virginia Dare, and she was the granddaughter of White.

There are three common themes I learned as a student in grade school that begat the founding of Anglo-America: God, Gold, and Glory -- "The Three G's." The first two permanent settlements in the English New World were Jamestown in present-day Virginia in 1607 by Captain Edward Maria Wingfield; and Plymouth in what is now Massachusetts in 1620. Both were founded upon completely different ideas, and yet they both fit the cliche of "The Three G's" I described perfectly: Jamestown was founded and thrived economically on the principle of Gold, creating the first vestiges of tobacco farming in 1614, and eventually slavery in Anglo-America in 1660. Plymouth was founded on the principle of religious freedom, something that the Protestant settlers desperately sought. They were referred to as "separatists" in England, but were officially known as, and led by, members of the religious congregations of Brownist English Dissenters due to their separation from the Church of England, the lone legally-recognized religious institution in the kingdom. They first migrated to Holland, where they attempted to established a church free and unfettered from the malevolent auspices of the government. However, the leaders of the separatists felt their offspring were growing up "too Dutch" -- by that meaning too libertine, a term defined today as "a dissolute person; usually a person who is morally unrestrained" -- and therefore were deviating off the path to Godly righteousness as well as losing their cultural identity as former English citizens. The separatists left Holland in September 1620, and the land that would become Plymouth Colony was sighted on the Mayflower approximately two months later.

The History of Native Americans and Their Relations with the U.S. Government As Represented by the Population Demographic of White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASP's)

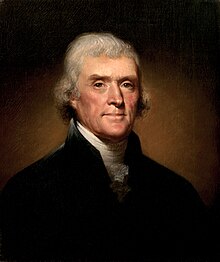

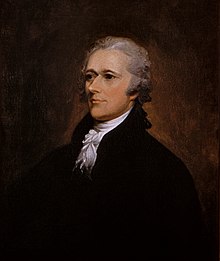

(Above: Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton -- the opposition co-founders of the first political party system. Courtesy of Wikipedia)

(Above: Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton -- the opposition co-founders of the first political party system. Courtesy of Wikipedia)

While the first inhabitants of the Americas were Native Americans, there is no recorded history known of the multitude of civilizations in the Western Hemisphere since the time of prehistory. It has been hypothesized, however, that prehistoric humans crossed the land bridge linking Siberia to present-day Alaska some 10,000 years ago, and from there, the early humanoid figures matriculated down the continents of North and South Americas. The issue with regards to relations between Anglo-Americans throughout the course of both Colonial America and the current government of the United States under the Constitution of 1787 has been one wanton of reconciliation. While there were periods of both peaceful cohabitation of adjacent lands by Native American tribes and white Anglo-American settlers, there have been equally as many conflicts resulting in bloodshed and mistrust between the two sides. Perhaps no other act of egregious discrimination that ultimately resulted in perhaps the most notorious known incident of genocide and ethnic cleaning manifested itself in the policy signed into law by President Andrew Jackson known as the Indian Removal Act. Despite being contested at the U.S. Supreme Court under the case heading Worcester v. Georgia (1832) and ruled illegal according to longtime Chief Justice John Marshall, President Jackson ignored his ruling, possibly stating a phrase that, while perhaps spurious in actuality, is perhaps the most famous of all Jacksonian quotations:

"John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it!"This is widely considered a derivative of a line in letter Jackson wrote to John Coffee upon reflecting on Marshall's ruling:

"...the decision of the Supreme Court has fell still born, and they find that they cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate...."Hence, the legacy of Andrew Jackson's style of politics, according to The Miller Center at the University of Virginia which conducts in-depth studies of the U.S. presidents, is summarized in the final two sentences of its biographical account on him:

"To admirers he stands as a shining example of American accomplishment, the ultimate individualist and democrat. To detractors he appears an incipient tyrant, the closest we have yet come to an American Caesar."

This does not take into consideration racial tensions which have ravaged America since the institution of slavery was initiated in 1660 in Jamestown. On that topic I will brief touch with this comment: African slaves who would be doomed to live as such capacity were immigrants as well, albeit by force of the European and later Anglo-American traders. An irony to be considered is this: while America was founded upon the principles of liberty based on "the Laws of Nature and Nature's God" according to Jefferson in his drafting of the Declaration of Independence, this only pertained to white males, for it was not until the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln's issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment that the institution of slavery ended. Even then, the fight for social equity continued for better than another century. To this day, the legacy of "the peculiar institution" looms as large as an overarching albatross over the heads of white and black civic leaders in their attempts to mend the fences of America's darkest historical detail. The same can be stated with regards to gender equity between men and women in society.

The Records of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton on the Principles of Immigration

Finally, we are on the present-day topic of immigration reform. The policy the Obama administration wishes to implement, through his subordinate lawmakers within the Democratic Party and those in the GOP like Sens. Lindsey Graham and Marco Rubio who would either agree to or offer limited acquiescence to the president's will, would provide unconditional, universal amnesty to all foreigners, including those who are classified as illegal aliens. The opposition from the Republicans has been weak and paltry, ranging from Sen. Ted Cruz's hardline stance that is demonstrated in the quote I provided earlier in this article, to Sen. Rand Paul, who is not discounting the policy is complete, utter folly, but rather as a proposed bill in need of reinforcements that he feels he can provide that would be able to bridge the gap between the Democratic-controlled Senate and the GOP-dominated House of Representatives. The presence of flimsiness on this issue that, if passed as it sets into law, would create 30 million new voters who would overwhelming caste their ballots for Democratic Party candidates as well as the still-more dangerous phenomena of depriving those who have are already naturalized citizens either by birth or through earning citizenship the legal and proper way the ability to readily find and compete for jobs based upon the tendencies of many of these immigrants who will have been granted unconditional, universal amnesty being willing to work for less pay. As the party that champions those they perceive to be the poor and underprivileged, minorities, and discriminated peoples of America, they are, by dent of promulgating to the masses their intent behind the spirit of this piece of legislation, promoting the perpetuation of poverty through the inevitable consequences of their actions rather than the falsehoods underlying their empty words. By keeping a large portion of the American population poor, which by Congress passing this bill and President Obama signing it into law, the levels of unemployment will rise among the people who already live here, increase among those who are granted amnesty, and among those who are granted amnesty that find work, will live below the poverty threshold; meanwhile, those who lose their jobs as a result of the willingness of the newly-amnestied illegal aliens as legal citizens will be fortunate to find occupations that pay what they earned at their old trades. It is a cruel irony, a "Catch-22" in reference to the famous Joseph Heller novel, that the party that always promises social equity by engaging in class warfare does so not by creating widespread wealth and opportunity, but by engendering further dependency by the American people to the mercies of the political Left in power in the federal government.

This issue of immigration is nothing new; in fact, it was a topic of great debate as early as the formative years of the republic. Jefferson, widely considered to be the most significant of the Founding Fathers in meticulously crafting and molding the modus operandi that would serve its posterity for centuries to come, spoke originally on the topic in his groundbreaking work, Notes on the State of Virginia (circa 1781). He states his opinion in Query 8: "Population" The number of its inhabitants? his first opinion on the matter:

"Population"The number of its inhabitants?

Population

The following table shews the number of persons imported for the establishment of our colony in its infant state, and the census of inhabitants at different periods, extracted from our historians and public records, as particularly as I have had opportunities and leisure to examine them. Successive lines in the same year shew successive periods of time in that year. I have stated the census in two different columns, the whole inhabitants having been sometimes numbered, and sometimes the tythes only. This term, with us, includes the free males above 16 years of age, and slaves above that age of both sexes. A further examination of our records would render this history of our population much more satisfactory and perfect, by furnishing a greater number of intermediate terms. Those however which are here stated will enable us to calculate, with a considerable degree of precision, the rate at which we have increased. During the infancy of the colony, while numbers were small, wars, importations, and other accidental circumstances render the progression fluctuating and irregular. By the year 1654, however, it becomes tolerably uniform, importations having in a great measure ceased from the dissolution of the company, and the inhabitants become too numerous to be sensibly affected by Indian wars. Beginning at that period, therefore, we find that from thence to the year 1772, our tythes had increased from 7209 to 153,000. The whole term being of 118 years, yields a duplication once in every 27 1/4 years. The intermediate enumerations taken in 1700, 1748, and 1759, furnish proofs of the uniformity of this progression. Should this rate of increase continue, we shall have between six and seven millions of inhabitants within 95 years. If we suppose our country to be bounded, at some future day, by the meridian of the mouth of the Great Kanhaway, (within which it has been before conjectured, are 64,491 square miles) there will then be 100 inhabitants for every square mile, which is nearly the state of population in the British islands.

-210-

Years Settlers imported. Census of Inabitants. Census of Tythes. 1607 100 40 120 1608 130 70 1609 490 16 60 1610 150 200 1611 3 ship loads 300 1612 80 1617 400 1618 200 40 600 1619 1216 1621 1300 1622 3800 2500 1628 3000 1632 2000 1644 4822 1645 5000 1652 7000 1654 7209 1700 22,000 1748 82,100 1759 105,000 1772 153,000 1782 567,614

Here I will beg leave to propose a doubt. The present desire of America is to produce rapid population by as great importations of foreigners as possible. But is this founded in good policy? The advantage proposed is the multiplication of numbers. Now let us suppose (for example only) that, in this state, we could double our numbers in one year by the importation of foreigners; and this is a greater accession than the most sanguine advocate for emigration has a right to expect. Then I say, beginning with a double stock, we shall attain any given degree of population only 27 years and 3 months sooner than if we proceed on our single stock. If we propose four millions and a half as a competent population for this state, we should be 54 1/2 years attaining it, could we at once double our numbers; and 81 3/4 years, if we rely on natural propagation, as may be seen by the following table.

In the first column are stated periods of 27 1/4 years; in the second are our numbers, at each period, as they will be if we proceed on our actual stock; and in the third are what they

-211-

would be, at the same periods, were we to set out from the double of our present stock.

Proceeding on our present stock. Proceeding on a double stock. 1781 567,614 1,135,228 1808 1/4 1,135,228 2,270,456 1835 1/2 2,270,456 4,540,912 1862 3/4 4,540,912

I have taken the term of four millions and a half of inhabitants for example's sake only. Yet I am persuaded it is a greater number than the country spoken of, considering how much inarrable land it contains, can clothe and feed, without a material change in the quality of their diet. But are there no inconveniences to be thrown into the scale against the advantage expected from a multiplication of numbers by the importation of foreigners? It is for the happiness of those united in society to harmonize as much as possible in matters which they must of necessity transact together. Civil government being the sole object of forming societies, its administration must be conducted by common consent. Every species of government has its specific principles. Ours perhaps are more peculiar than those of any other in the universe. It is a composition of the freest principles of the English constitution, with others derived from natural right and natural reason. To these nothing can be more opposed than the maxims of absolute monarchies. Yet, from such, we are to expect the greatest number of emigrants. They will bring with them the principles of the governments they leave, imbibed in their early youth; or, if able to throw them off, it will be in exchange for an unbounded licentiousness, passing, as is usual, from one extreme to another. It would be a miracle were they to stop precisely at the point of temperate liberty. These principles, with their language, they will transmit to their children. In proportion to their numbers, they will share with us the legislation. They will infuse into it their spirit, warp and bias its direction, and render it a heterogeneous, incoherent, distracted mass. I may appeal to experience, during the present contest, for a verification of these conjectures. But, if they be not certain in event, are they not

-212-

possible, are they not probable? Is it not safer to wait with patience 27 years and three months longer, for the attainment of any degree of population desired, or expected? May not our government be more homogeneous, more peaceable, more durable? Suppose 20 millions of republican Americans thrown all of a sudden into France, what would be the condition of that kingdom? If it would be more turbulent, less happy, less strong, we may believe that the addition of half a million of foreigners to our present numbers would produce a similar effect here. If they come of themselves, they are entitled to all the rights of citizenship: but I doubt the expediency of inviting them by extraordinary encouragements. I mean not that these doubts should be extended to the importation of useful artificers. The policy of that measure depends on very different considerations. Spare no expence in obtaining them. They will after a while go to the plough and the hoe; but, in the mean time, they will teach us something we do not know. It is not so in agriculture. The indifferent state of that among us does not proceed from a want of knowledge merely; it is from our having such quantities of land to waste as we please. In Europe the object is to make the most of their land, labour being abundant: here it is to make the most of our labour, land being abundant.

It will be proper to explain how the numbers for the year 1782 have been obtained; as it was not from a perfect census of the inhabitants. It will at the same time develope the proportion between the free inhabitants and slaves. The following return of taxable articles for that year was given in.

53,289 free males above 21 years of age. 211,698 slaves of all ages and sexes. 23,766 not distinguished in the returns, but said to be titheable slaves. 195,439 horses. 609,734 cattle. 5,126 wheels of riding-carriages. 191 taverns.

There were no returns from the 8 counties of Lincoln, Jefferson, Fayette, Monongalia, Yohogania, Ohio, Northampton, and York. To find the number of slaves which should

-213-

have been returned instead of the 23,766 titheables, we must mention that some observations on a former census had given reason to believe that the numbers above and below 16 years of age were equal. The double of this number, therefore, to wit, 47,532 must be added to 211,698, which will give us 259,230 slaves of all ages and sexes. To find the number of free inhabitants, we must repeat the observation, that those above and below 16 are nearly equal. But as the number 53,289 omits the males between 16 and 21, we must supply them from conjecture. On a former experiment it had appeared that about one-third of our militia, that is, of the males between 16 and 50, were unmarried. Knowing how early marriage takes place here, we shall not be far wrong in supposing that the unmarried part of our militia are those between 16 and 21. If there be young men who do not marry till after 21, there are as many who marry before that age. But as the men above 50 were not included in the militia, we will suppose the unmarried, or those between 16 and 21, to be one-fourth of the whole number above 16, then we have the following calculation:

53,289 free males above 21 years of age. 17,763 free males between 16 and 21. 71,052 free males under 16. 142,104 free females of all ages. -- -- -- - 284,208 free inhabitants of all ages. 259,230 slaves of all ages. -- -- -- - 543,438 inhabitants,

exclusive of the 8 counties from which were no returns. In these 8 counties in the years 1779 and 1780 were 3,161 militia. Say then,

3,161 free males above the age of 16. 3,161 ditto under 16. 6,322 free females. -- -- -- 12,644 free inhabitants in these 8 counties.

To find the number of slaves, say, as 284,208 to 259,230, so is 12,644 to 11,532. Adding the third of these numbers to the first, and the fourth to the second, we have,

296,852 free inhabitants. 270,762 slaves. -- -- -- - 567,614 inhabitants of every age, sex, and condition.

But

-214-