Introduction: A Brief Description of the Popular Stereotypes Political Leaders in the GOP and Democratic Parties Endure, Leading Into the Perception of the Democratic Party's Historical Preponderance for Weak Foreign Policies

Within the realm of American politics exists a slew of stereotypes associated with both of the major political parties. Republicans are considered racists and bigots by the Left because they often choose to cut funding for government entitlement programs at nearly every level of our federal system of government. In contrast to this charge, the Democrats are touted by the media to be the champions of the poor and underprivileged, for the common man. This has been a prevailing archetype associated with the party since its founding in 1828. Republicans are considered by the masses to be the party promoting limited government and a strong military presence for providing the national defense. The Democrats are frequently viewed as "peaceniks" "hippies," especially since the 1960's social revolutions, bent on operating through bargaining and diplomacy in order to solve foreign disputes between two foreign nations, up to and including the United States itself. Republicans are considered the party that attempts to take the moral high ground that is perceived to be steeped greatly in religiosity, while Democrats are often thought as godless and amoral. Finally, Republicans are thought to be the party that is repressive to the civil rights and liberties of minorities, women, and homosexuals, while the Democrats will do just about anything to placate to these segments of the population in order to build the foundation upon which they can establish power and legitimacy through the democratic process.

It is so easy for Democrats to win elections -- far easier for them, in fact, than it is for members of the GOP. First, when they promise to "make the rich pay their fair share" of the tax burden, which in U.S. history has been as high as 94% of the incomes of the wealthiest Americans (1944), the poor and impoverished voters listen closely as if there is blood in the water. Then, the Democrats promise not to increase the taxes of the middle-class, which draws many people from that income demographic to their side. Finally, when the Democrats decide there is not enough money despite high tax rates for nearly every level of income, the middle-class's tax burden is increased significantly, further enthralling to small portion of American society below the poverty line. When the economy shows signs of some life if the nation happens to be in the midst of a recession, the Democrats take all the credit for the reported "progress" by claiming they are leveling the gap between the richest Americans and the poorest; thus, we have the concept of class-warfare that was first experimented with during the French Revolution by radical left-wing political partisans, and later by the astounding number of Communist revolutions such as in Russia, China, Korea, Cuba, and Vietnam between 1917 and 1975 with the fall of Saigon. Playing the class-warfare card by stating that the richest Americans, most of whom are wealthy white "aristocratic" male types, present a clear and present danger to economic and financial health and prosperity of the impoverished collective is key to the Democrats' political platform. And when the members of the poorest income brackets of Americans happen to be poor inner city African-Americans or Hispanics, regardless of whether or not they are legalized citizens of the U.S., they are nearly guaranteed to scarf up votes from that collective, for it is the concept of the collective of poor, oppressed working class folks who live off of meager wages as the result of the failings of capitalism, or what Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels referred to as the proletariat in their renowned socio-economic and political book called The Communist Manifesto that perpetuates this myth of class-warfare and popular discord. The poor are the salt of the earth, and the greatest source of power and legitimacy from which the Democrats may derive.

The most common stereotype regarding the Democratic Party, however, is this one: they focus almost solely on domestic issues such as the delicate balance of the progressive income tax that has existed in the U.S. since the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1912; the federal entitlement programs that have been rather commonplace since the FDR administration; the promotion of greater civil liberties even if it costs another person to lose theirs (see Roe v. Wade, which legalized the practice of abortions which, without a doubt, violates the right of the unborn child that was living at conception the to life, liberty, and the pursuits of happiness and property); Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid; civil rights to the point where Caucasian males are punished for being what they are born to be: white and free; and so on and so forth. The Democrats aim to engender a culture of dependency and, ultimately, personal irresponsibility among the American people, for if the people are willing to pay just a little bit more in the way of their hard-earned wages to the federal government, it will take care of them. Sadly, as many have read about the economic and fiscal record of FDR, Truman, Carter, and now Obama, socializing America economically and through the implementation of welfare programs does not create wealth or opportunity, but it does level the income playing field to the point where the poor become poorer so long as the wealthiest Americans are made to suffer as well. This phenomena has rarely been realized by the majority of American voters and taxpayers since 1912, which with the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment also came the birth of big government in the U.S. Furthermore, Democrats over the course of the past 80 years are rather friendly to the influx of immigrants regardless of whether or not they are here legally. Throughout the history of this great democratic-republic, the greatest influence on America's political climate and atmosphere have been in the form of incoming immigrants who bring their political ideologies with them from their homelands. And it is no coincidence that the immigrants from 1877 through about the end of World War I originated the Gilded Age political coalitions of Populists and Progressives -- the fledgling years of modern day liberal politics as we know it today.

Along with stereotypes of tending to domestic issues comes two that the general consensus among political scientists at which the Democrats are abject failures, and those are the concepts of foreign policy and national defense. Since the dawn of modern-day liberalism near the end of the 19th Century, the concept of the proletariat whose natural rights have been violated by the evil trappings of capitalism has prevailed almost to the exclusion of the U.S. being a world economic and military power that became our role as part of the spoils of victory from the Spanish-American War of 1898. The leader of the Populist Party wing of the Democratic Party William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska was an advocate of war against Spain in 1898. Historian William Leuchtenburg described Bryan as "few political figures exceeded the enthusiasm of William Jennings Bryan for the Spanish war." Bryan indeed argued that:

The Populists predicated their platform on the plight of farmers. Like today's Democratic Party, it catered to poor, white cotton farmers in the South (especially North Carolina, Alabama, and Texas) and hard-pressed wheat farmers in the plains states (especially Kansas and Nebraska), it represented a radical crusading form of agrarianism and hostility to banks, railroads, and elites generally. It sometimes formed coalitions with labor unions, and in 1896 the Democrats endorsed their presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan. The terms "populist" and "populism" are commonly used for anti-elitist appeals in opposition to established interests and mainstream parties. Thus, it was one of the very first political platforms in the U.S. to propagate the phenomenon of class-warfare.

The Progressive Era based its modus operandi in part on that of the Populist Party, but there were key differences. The era was a period of social activism and political reform in the United States that flourished from the 1890's to the 1920's. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political machines and bosses. Many (but not all) Progressives supported prohibition in order to destroy the political power of local bosses based in saloons. At the same time, women's suffrage was promoted to bring a "purer" female vote into the arena. A second theme was building an Efficiency movement in every sector that could identify old ways that needed modernizing, and bring to bear scientific, medical and engineering solutions. Many activists joined efforts to reform local government, public education, medicine, finance, insurance, industry, railroads, churches, and many other areas. Progressives transformed, professionalized and made "scientific" the social sciences, especially history, economics, and political science. In academic fields the day of the amateur author gave way to the research professor who published in the new scholarly journals and presses. The national political leaders included Theodore Roosevelt, Robert M. La Follette, Sr., Charles Evans Hughes and Herbert Hoover on the Republican side, and William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson and Al Smith on the Democratic side. Initially the movement operated chiefly at local levels; later it expanded to state and national levels. Progressives drew support from the middle class, and supporters included many lawyers, teachers, physicians, ministers and business people. The Progressives strongly supported scientific methods as applied to economics, government, industry, finance, medicine, schooling, theology, education, and even the family. They closely followed advances underway at the time in Western Europe and adopted numerous policies, such as a major transformation of the banking system by creating the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Reformers felt that old-fashioned ways meant waste and inefficiency, and eagerly sought out the "one best system."

If one is to draw a conclusion as to the practice of foreign policy Progressive leaders implemented during this, one needs to study the history of presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. Although both were Progressive, they were members of separate political parties, as stated above.

In describing Roosevelt's foreign policy, his biographer and noted Italian historian William Roscoe Thayer (1859-1927) wrote this about him in Theodore Roosevelt: An Intimate Biography:

The armed conflicts with ** indicate those in which a Republican president spent some of the time during the conflict in office. Note that there have been far more conflicts fought during the Democratic presidents time in the White House, not to mention hundreds of thousands of more deaths.

During the Obama administration, military casualties in Afghanistan have doubled in comparison to the number sustained during the eight year President George W. Bush served. Also, take into consideration that Obama has successfully alienated Israel, as he is too busy trying to become chummy with Arab nations sponsored by terrorists, most notably Syria, where the Republican Obama supporter Sen. John McCain is pushing for the president's intervention into the Syrian rebels' plight. Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), however, is against this tactic, claiming that will be, in essence, arming allies of al-Qaeda who would, in turn, persecute the nation's 2 million Christians. That is nothing new, however, as it is widely believed by conservatives that the president is not only not interested in the interests in Christians in the U.S. and around the world, but that his secret life as a Muslim drives him to hate Christians and thus to surreptitiously suppress them. His failures to properly withdraw from Iraq have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Iraqi civilians though terrorist attacks and mob violence. And his handling of a post-bin Laden al-Qaeda has been atrocious, resulting in the attacks at the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya by their operatives, which he attempted to cover up.

President Obama is the latest in a long line of Democrats who have pursued aggressive foreign policies. Woodrow Wilson promised the American people, and even implored with them not to take sides in the conflict, that he would not enter the nation into World War I; he did, in one year, better than 116,000 troops paid the ultimate price. It is believed by some conservatives that FDR lured the Japanese into attacking the U.S. Naval based at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 costing the lives of close to 3,000 American naval officiers, though the Left has almost successfully defended the founder of the modern liberal ideology's honor. Not withstanding, the U.S. sustained over 400,000 deaths during the war. Harry S. Truman was responsible for allowing the Cold War to being, allowing mainland China to be won by the Communists led by Mao Zedong, and failed to defeat the People's Army of North Korea under the leadership of Kim Il-Sung by failing to provide the proper manpower to push the Communists back across the 38th Parallel; firing Gen. Douglas MacArthur did not help his cause, either, as that reflected poorly on his approval rating; 36,000 or so died in that conflict, with no real victory obtained from it. JFK was only successful in one instance of his foreign policy, that of course being with the Cuban Missile Crisis. Lyndon Johnson escalated the Vietnam War by increasing the number of troops from 16,000 at the beginning of his presidency in 1964 to 550,000 in 1968, and he was thus responsible for most of the 58,000+ troops killed. Jimmy Carter's only successful venture during his entire presidency was the Camp David Accord where he negotiated a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. His greatest failure, perhaps greater than his handling of the economy, was his dealing with the Iran hostages crisis; it took until Ronald Reagan was sworn into office before the hostages would be released, which was just hours after Carter left the White House. Finally, President Clinton used the bombings of Iraq and the former Yugoslavia throughout the 1990's to cover up the scandal over Monica Lewinsky on network television, and he sold nuclear secrets to the Chinese government, as stated above, which is tantamount to treason.

Before you believe anything the Left claims about Republicans -- that all Republicans are "war mongers" -- please share with them this history of warfare during the course of the past 115 years. Progressives, one of the two precursors to the modern platform of the Democratic Party along with the Populists, are more interested in imperialistic ventures around the world than are Republicans, and have been historically for the majority of that period of time.

The Philosophies on Foreign Policy for the Progressive Movement and the People's (Populist) Party: The Genesis of the Modern Democratic Party in America's Modern Foreign Affairs Platform

Along with stereotypes of tending to domestic issues comes two that the general consensus among political scientists at which the Democrats are abject failures, and those are the concepts of foreign policy and national defense. Since the dawn of modern-day liberalism near the end of the 19th Century, the concept of the proletariat whose natural rights have been violated by the evil trappings of capitalism has prevailed almost to the exclusion of the U.S. being a world economic and military power that became our role as part of the spoils of victory from the Spanish-American War of 1898. The leader of the Populist Party wing of the Democratic Party William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska was an advocate of war against Spain in 1898. Historian William Leuchtenburg described Bryan as "few political figures exceeded the enthusiasm of William Jennings Bryan for the Spanish war." Bryan indeed argued that:

"...universal peace cannot come until justice is enthroned throughout the world. Until the right has triumphed in every land and love reigns in every heart, government must, as a last resort, appeal to force."But he also opposed the U.S. becoming an imperial power. In the speech he delivered during the Democratic National Convention of 1900 titled "The Paralyzing Influence of Imperialism," he discussed his views behind his opposition to the annexation of the Philippines despite his support for the Treaty of Paris of 1898 that ended the war, and questioned the U.S.'s right to overpower people of another country just for a military base. He mentioned too, at the beginning of the speech, that the United States should not try to emulate the imperialism of Great Britain and other European countries.

The Populists predicated their platform on the plight of farmers. Like today's Democratic Party, it catered to poor, white cotton farmers in the South (especially North Carolina, Alabama, and Texas) and hard-pressed wheat farmers in the plains states (especially Kansas and Nebraska), it represented a radical crusading form of agrarianism and hostility to banks, railroads, and elites generally. It sometimes formed coalitions with labor unions, and in 1896 the Democrats endorsed their presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan. The terms "populist" and "populism" are commonly used for anti-elitist appeals in opposition to established interests and mainstream parties. Thus, it was one of the very first political platforms in the U.S. to propagate the phenomenon of class-warfare.

The Progressive Era based its modus operandi in part on that of the Populist Party, but there were key differences. The era was a period of social activism and political reform in the United States that flourished from the 1890's to the 1920's. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political machines and bosses. Many (but not all) Progressives supported prohibition in order to destroy the political power of local bosses based in saloons. At the same time, women's suffrage was promoted to bring a "purer" female vote into the arena. A second theme was building an Efficiency movement in every sector that could identify old ways that needed modernizing, and bring to bear scientific, medical and engineering solutions. Many activists joined efforts to reform local government, public education, medicine, finance, insurance, industry, railroads, churches, and many other areas. Progressives transformed, professionalized and made "scientific" the social sciences, especially history, economics, and political science. In academic fields the day of the amateur author gave way to the research professor who published in the new scholarly journals and presses. The national political leaders included Theodore Roosevelt, Robert M. La Follette, Sr., Charles Evans Hughes and Herbert Hoover on the Republican side, and William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson and Al Smith on the Democratic side. Initially the movement operated chiefly at local levels; later it expanded to state and national levels. Progressives drew support from the middle class, and supporters included many lawyers, teachers, physicians, ministers and business people. The Progressives strongly supported scientific methods as applied to economics, government, industry, finance, medicine, schooling, theology, education, and even the family. They closely followed advances underway at the time in Western Europe and adopted numerous policies, such as a major transformation of the banking system by creating the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Reformers felt that old-fashioned ways meant waste and inefficiency, and eagerly sought out the "one best system."

If one is to draw a conclusion as to the practice of foreign policy Progressive leaders implemented during this, one needs to study the history of presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. Although both were Progressive, they were members of separate political parties, as stated above.

The Foreign Policy of Theodore Roosevelt

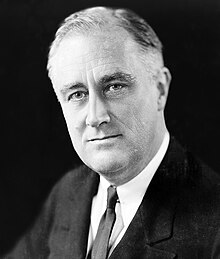

(Above: President Theodore Roosevelt, served from 1901-1909. Courtesy of Wikipedia)

In describing Roosevelt's foreign policy, his biographer and noted Italian historian William Roscoe Thayer (1859-1927) wrote this about him in Theodore Roosevelt: An Intimate Biography:

IN taking the oath of office at Buffalo, Roosevelt promised to continue President McKinley’s policies. And this he set about doing loyally. He retained McKinley’s Cabinet, 1 who were working out the adjustments already agreed upon. McKinley was probably the best-natured President who ever occupied the White House. He instinctively shrank from hurting anybody’s feelings. Persons who went to see him in dudgeon, to complain against some act which displeased them, found him “a bower of roses,” too sweet and soft to be treated harshly. He could say “no” to applicants for office so gently that they felt no resentment. For twenty years he had advocated a protective tariff so mellifluously, and he believed so sincerely in its efficacy, that he could at any time hypnotize himself by repeating his own phrases. If he had ever studied the economic subject, it was long ago, and having adopted the tenets which an Ohio Republican could hardly escape from adopting, he never revised them or even questioned their validity. His protectionism, like cheese, only grew stronger with age. As a politician, he was so hospitable that in the campaign of 1896, which was fought to maintain the gold standard and the financial honesty of the United States, he showed very plainly that he had no prejudice against free silver, and it was only at the last moment that the Republican managers could persuade him to take a firm stand for gold.

The chief business which McKinley left behind him, the work which Roosevelt took up and carried on, concerned Imperialism. The Spanish War forced this subject to the front by leaving us in possession of the Philippines and by bequeathing to us the responsibility for Cuba and Porto Rico. We paid Spain for the Philippines, and in spite of constitutional doubts as to how a Republic like the United States could buy or hold subject peoples, we proceeded to conquer those islands and to set up an American administration in them. We also treated Porto Rico as a colony, to enjoy the blessing of our rule. And while we allowed Cuba to set up a Republic of her own, we made it very clear that our benevolent protection was behind her.

All this constituted Imperialism, against which many of our soberest citizens protested. They alleged that as a doctrine it contradicted the fundamental principles on which our nation was built. Since the Declaration of Independence, America had stood before the world as the champion and example of Liberty, and by our Civil War she had purged her self of Slavery. Imperialism made her the mistress of peoples who had never been consulted. Such moral inconsistency ought not to be tolerated. In addition to it was the political danger that lay in holding possessions on the other side of the Pacific. To keep them we must be prepared to defend them, and defense would involve maintaining a naval and military armament and of stimulating a warlike spirit, repugnant to our traditions. In short, Imperialism made the United States a World Power, and laid her open to its perils and entanglements.

But while a minority of the men and women of sober judgment and conscience opposed Imperialism, the large majority accepted it, and among these was Theodore Roosevelt. He believed that the recent war had involved us in a responsibility which we could not evade if we would. Having destroyed Spanish sovereignty in the Philippines, we must see to it that the people of those islands were protected. We could not leave them to govern themselves because they had no experience in government; nor could we dodge our obligation by selling them to any other Power. Far from hesitating because of legal or moral doubts, much less of questioning our ability to perform this new task, Roosevelt embraced Imperialism, with all its possible issues, boldly not to say exultantly. To him Imperialism meant national strength, the acknowledgment by the American people that the United States are a World Power and that they would not shrink from taking up any burden which that distinction involved.

When President Cleveland, at the end of 1895, sent his swingeing message in regard to the Venezuelan Boundary quarrel, Roosevelt was one of the first to foresee the remote consequences. And by the time he himself became President, less than six years later, several events—our taking of the Hawaiian Islands, the Spanish War, the island possessions which it saddled upon us—confirmed his conviction that the United States could no longer live isolated from the great interests and policies of the world, but must take their place among the ruling Powers. Having reached national maturity we must accept Expansion as the logical and normal ideal for our matured nation. Cleveland had laid down that the Monroe Doctrine was inviolable; Roosevelt insisted that we must not only bow to it in theory, but be prepared to defend it if necessary by force of arms.

Very naturally, therefore, Roosevelt encouraged the passing of legislation needed to complete the settlement of our relations with our new possessions. He paid especial attention to the men he sent to administer the Philippines, and later he was able to secure the services of W. Cameron Forbes as Governor-General. Mr. Forbes proved to be a Viceroy after the best British model and he looked after the interest of his wards so honestly and competently that conditions in the Philippines improved rapidly, and the American public in general felt no qualms over possessing them. But the Anti-Imperialists, to whom a moral issue does not cease to be moral simply because it has a material sugar-coating, kept up their protest.

There were, however, matters of internal policy; along with them Roosevelt inherited several foreign complications which he at once grappled with. In the Secretary of State, John Hay, he had a remarkable helper. Henry Adams told me that Hay was the first “man of the world” who had ever been Secretary of State. While this may be disputed, nobody can fail to see some truth in Adams’s assertion. Hay had not only the manners of a gentleman, but also the special carriage of a diplomat. He was polite, affable, and usually accessible, without ever losing his innate dignity. An indefinable reserve warded off those who would either presume or indulge in undue familiarity His quick wits kept him always on his guard. His main defect was his unwillingness to regard the Senate as having a right to pass judgment on his treaties. And instead of being compliant and compromising, he injured his cause with the Senators by letting them see too plainly that he regarded them as interlopers, and by peppering them with witty but not agreeable sarcasm. In dealing with foreign diplomats, on the other hand, he was at his best. They found him polished, straightforward, and urbane. He not only produced on them the impression of honesty, but he was honest. In all his diplomatic correspondence, whether he was writing confidentially to American representatives or was addressing official notes to foreign governments, I do not recall a single hint of double-dealing. Hay was the velvet glove, Roosevelt the hand of steel.

For many years Canada and the United States had enjoyed grievances towards each other, grievances over fisheries, over lumber, and other things, no one of which was worth going to war for. The discovery of gold in the Klondike, and the rush thither of thousands of fortune-seekers, revived the old question of the Alaskan Boundary; for it mattered a great deal whether some of the gold-fields were Alaskan—that is, American-or Canadian. Accordingly, a joint High Commission was appointed towards the end of McKinley’s first administration to consider the claims and complaints of the two countries. The Canadians, however, instead of settling each point on its own merits, persisted in bringing in a list of twelve grievances which varied greatly in importance, and this method favored trading one claim against another. The result was that the Commission, failing to agree, disbanded. Nevertheless, the irritation continued, and Roosevelt, having become President, and being a person who was constitutionally opposed to shilly-shally, suggested to the State Department that a new Commission be appointed under conditions which would make a decision certain. He even went farther, he took precautions to assure a verdict in favor of the United States. He appointed three Commissioners—Senators Lodge, Root, and Turner; the Canadians appointed two, Sir A. L. Jette and A. B. Aylesworth; the English representative was Alverstone, the Lord Chief Justice.

The President gave to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, of the Supreme Court, who was going abroad for the summer, a letter which he was “indiscreetly” to show Mr. Chamberlain, Mr. Balfour, and two or three other prominent Englishmen. In this letter he wrote:

|

During the Obama administration, military casualties in Afghanistan have doubled in comparison to the number sustained during the eight year President George W. Bush served. Also, take into consideration that Obama has successfully alienated Israel, as he is too busy trying to become chummy with Arab nations sponsored by terrorists, most notably Syria, where the Republican Obama supporter Sen. John McCain is pushing for the president's intervention into the Syrian rebels' plight. Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), however, is against this tactic, claiming that will be, in essence, arming allies of al-Qaeda who would, in turn, persecute the nation's 2 million Christians. That is nothing new, however, as it is widely believed by conservatives that the president is not only not interested in the interests in Christians in the U.S. and around the world, but that his secret life as a Muslim drives him to hate Christians and thus to surreptitiously suppress them. His failures to properly withdraw from Iraq have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Iraqi civilians though terrorist attacks and mob violence. And his handling of a post-bin Laden al-Qaeda has been atrocious, resulting in the attacks at the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya by their operatives, which he attempted to cover up.

President Obama is the latest in a long line of Democrats who have pursued aggressive foreign policies. Woodrow Wilson promised the American people, and even implored with them not to take sides in the conflict, that he would not enter the nation into World War I; he did, in one year, better than 116,000 troops paid the ultimate price. It is believed by some conservatives that FDR lured the Japanese into attacking the U.S. Naval based at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 costing the lives of close to 3,000 American naval officiers, though the Left has almost successfully defended the founder of the modern liberal ideology's honor. Not withstanding, the U.S. sustained over 400,000 deaths during the war. Harry S. Truman was responsible for allowing the Cold War to being, allowing mainland China to be won by the Communists led by Mao Zedong, and failed to defeat the People's Army of North Korea under the leadership of Kim Il-Sung by failing to provide the proper manpower to push the Communists back across the 38th Parallel; firing Gen. Douglas MacArthur did not help his cause, either, as that reflected poorly on his approval rating; 36,000 or so died in that conflict, with no real victory obtained from it. JFK was only successful in one instance of his foreign policy, that of course being with the Cuban Missile Crisis. Lyndon Johnson escalated the Vietnam War by increasing the number of troops from 16,000 at the beginning of his presidency in 1964 to 550,000 in 1968, and he was thus responsible for most of the 58,000+ troops killed. Jimmy Carter's only successful venture during his entire presidency was the Camp David Accord where he negotiated a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. His greatest failure, perhaps greater than his handling of the economy, was his dealing with the Iran hostages crisis; it took until Ronald Reagan was sworn into office before the hostages would be released, which was just hours after Carter left the White House. Finally, President Clinton used the bombings of Iraq and the former Yugoslavia throughout the 1990's to cover up the scandal over Monica Lewinsky on network television, and he sold nuclear secrets to the Chinese government, as stated above, which is tantamount to treason.

Before you believe anything the Left claims about Republicans -- that all Republicans are "war mongers" -- please share with them this history of warfare during the course of the past 115 years. Progressives, one of the two precursors to the modern platform of the Democratic Party along with the Populists, are more interested in imperialistic ventures around the world than are Republicans, and have been historically for the majority of that period of time.

No comments:

Post a Comment